Church History and Modern Worship (Part One) — 10,000 Fathers Worship School

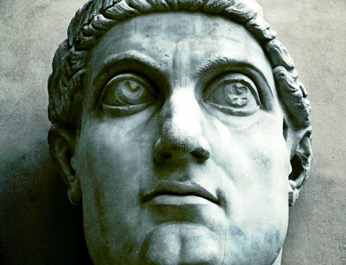

Constantine was a complex character; one who was named a pagan god but also a saint by the Eastern church. He led the cessation of persecution for Christians but also contributed to a culture of simony and corruption. Whether or not Constantine’s contribution was for the benefit of the Church depends on who you ask. Nevertheless, wherever you stand on the life of Constantine, you cannot dismiss the giant impact he’s had on the Christian faith and specifically on worship. In fact, John O’ Malley has claimed Constantine was, with the exception of Peter, more important for the papacy and for Christianity than any pope.

When studying Church history, we find Constantine was just as mysterious of a character for the early Christians. There were two main views pertaining to the life of the emperor: one that held him in high regard and the other that held suspicion towards him. First, there were those such as Eusebius – the first Church historian – who believed that Constantine’s conversion was the goal toward which the history of the Church and the Empire had always been moving. For these people, Constantine was chosen by God; an instrument of the divine design. Second, there were those who claimed that Constantine was simply a shrewd politician who found many advantages to be drawn from a “conversion.” These people saw the rise of Constantine and the imperial Church as an abomination. Many of them began to withdraw from the Church at large.

I believe each of these views, no doubt, are exaggerated. Constantine was too complex a character to definitively label good or evil, however (whether he’s a saint or something else) there is no avoiding our modern worship would not be the same without him. I would even go so far as to say that we are currently in a “Constantinian Age” of worship.

I believe the Church has recently returned to a form of worship that is very Constantinian in nature. In order to understand what I mean when I say we are presently in a Constantinian Age of Worship, we must first examine Constantine’s historical contribution to the life of worship in the Church.

When Constantine came to power as emperor in 306 C.E., a shift took place. A Church once persecuted became a privileged people. Christians no longer had to live in hiding, but were given power and prestige as the Imperial Church emerged. Sunday became one of the major days in the Church calendar after Constantine made it a day of civic as well as religious worship. House churches began to fade as elaborate (and expensive) basilicas were built. Financial privileges such as tax exemption were given to clergy, which in many cases led to the corruption of the Church. The line between civic and ecclesial authority blurred as the union of Church and State led to the secularization of the Church. The mass conversions of pagans contributed towards the paganization of worship. Sound familiar? One can easily see how each of these things caused a ripple effect in the Church that we are still feeling today. But perhaps the most significant Constantinian contribution to our current age of worship was the shift from a simple, democratic approach to worship to a more aristocratic liturgy.

Being that the Church had become so closely connected with the monarchical state, the worship itself was becoming more aristocratic, and a sharp distinction between the clergy and laity was defined. With the rise of choirs and processionals came the decline of the congregation’s role in worship. The result was a stricter hierarchical structure in the Church: one in which the Roman Bishop took supremacy over all other bishops. It was at this time the congregation began the practice of kneeling for prayer. As Justo L. Gonzalez states, “At an earlier time, the practice was not to kneel for prayer on Sundays, for that is the day of our adoption, when we approach the throne of the Most High as children and heirs to the Great King. Now after Constantine, one always knelt for prayer, as petitioners usually knelt before the emperor.” Converts began to flood the Church as Constantine continued to bestow favor upon it. Overwhelmed with the number of converts, the Church couldn’t properly disciple each one before their baptism, leading to the increase of syncretism and superstition. In other words, worship became so complex that the laity’s role was almost non-existent and the idea of a priesthood of all believers was all but forgotten.